Post-disaster Rehabilitation in Tharangambadi: People-based Model

- Benny Kuriakose

- Dec 21, 2021

- 22 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2022

It has been widely acknowledged that in most post disaster reconstruction, the level of participation of the beneficiaries in the design and the actual construction processes determine the success of such projects. This paper discusses the conscious effort to involve the beneficiaries in a post tsunami reconstruction project, through a concerted attempt to customize the design of the individual houses by involving the beneficiaries in both the design and construction process.

List Of Contents

1.1 Government Policy

In the aftermath of the tsunami that struck on 26th December 2004, the housing reconstruction policy was framed by the Government of Tamil Nadu, South India in which the following guidelines were given for the implementation of a massive housing reconstruction programme for the tsunami-affected families.

1. Houses located within 200 meters of the High Tide Line

As per the Coastal Regulation Zone notifications, only repair of structures authorized prior to 1991 is permissible and no new construction is possible. All the house owners of the fully damaged and partly damaged houses will be given the choice of going beyond 200 meters and would be eligible for a constructed house worth Rs. 150,000 free of cost.

Those who do not choose to do so will be permitted to undertake the repairs on their own in the existing locations, but they will not be provided with any assistance from the Government.

Even for houses, which are not damaged, the owners would be given the option of getting a new house beyond 200 meters.

2. Houses located between 200 meters and 500 meters of the High Tide Line

For the fully/partly damaged kutcha and fully damaged pucca houses in the area between 200 to 500 meters of the High Tide Line, new houses would be constructed beyond 500 meters of the High Tide Line.

If they are not willing to move beyond 500 meters of the High Tide Line, the houses for them will be constructed in the existing locations.

For the repair of the partly damaged pucca houses, financial assistance will be provided by the Government based on the assessment of the damage by a technical team.

The Government sought the assistance of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) for the reconstruction of houses in all the affected villages. South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies (SIFFS), one of the local NGOs had undertaken the reconstruction efforts in Tarangambadi with the assistance of international NGOs. SIFFS has been working in the marine fisheries sector for the last 25 years and is the apex body of organizations of small-scale artisan fish workers. A total of 1200 houses in Tarangambadi were to be rebuilt by SIFFS of which 451 houses were handed over in 2007 and the rest were under different stages of construction. This paper is based on the study of these 451 houses.

1.2 Tarangambadi: Demography

Tarangambadi is a village in Nagapattinam district of the East Coast of Tamil Nadu in South India. Tarangambadi is predominantly a fishing community of more than 1000 families with some non-fishing hamlets such as Vellipalayam, Pudu Palayam, Kesavan Palayam and Karan Street etc.

The demographic details and the damages caused by the tsunami are given in Table 1 below.

Prior to 26th December 2004, the risk caused by a tsunami or other natural hazards such as cyclones, floods, earthquakes etc., were not considered significant by the community. The tsunami raised the concern of the community, NGO’s, government and professionals about the possible impact of a larger tsunami in future. Although floods were common in the low lying areas of the village, tsunami waves with their high energy forced many people to think about relocating to a new site.

2.0 Housing Reconstruction- An Alternate Approach

2.1 Approaches to Reconstruction

Several approaches have been used for post disaster reconstruction of houses in various countries. Jennifer Duyne Barenstein (2006), based on her research in the post disaster reconstruction after the Gujarat earthquake, states that approaches can be broadly classified into five namely, owner driven approach, subsidiary housing approach, participatory housing approach, contractor driven construction in situ and contractor driven construction ex nihilo which are described in Table 2.

These approaches can be broadly classified as either owner driven approaches or contractor driven approaches. The participation of the community and the beneficiaries in these approaches could be at various levels. But generally, participation is least in the case of the contractor driven approach. Here we discuss a different approach followed by SIFFS in the post tsunami reconstruction project.

2.2 SIFFS’ Approach to Housing

SIFFS in its attempt to build houses paid attention not merely to housing, but also in addressing the livelihood requirements of the community. Issues like reducing the vulnerability against future tsunamis and recurring cyclones and also customizing the house taking into account the needs and aspirations of each house owner were systematically addressed. SIFFS then worked out a strategy based on the following principles;

The participation of the people in the layout of the village, design of the house and construction was essential.

The social and cultural aspects of the people concerned in the context of occupational and familial needs were taken into account.

An ownership feeling should be created among the house owners in the overall housing process.

In the case of many mass housing projects, the house owners modify their new homes immediately after occupancy. This need to personalize their new house is explained in part by the lack of customizability in housing design at the planning stage (Noguchi et al, 2005). In the SIFFS project, the house owners had the option to choose from one of the seven models designed and customize some aspects without modifying the structural system of the unit. The reason for the limited extent of customization was to minimize the changes to the house once handed over to them.

A strategy was formulated that involved extensive community participation in all stages of the construction, ranging from taking an informed choice on the location of their house to the planning, design, implementation and monitoring of the construction process. Since there was no financial contribution on the part of the house owners, community participation assumes more importance. For SIFFS constructing 1200 houses was a mammoth task. But when the organization of construction was decentralized, it became manageable. The whole project was divided into clusters of 25-35 houses which were managed by a committee of the house owners, community development officer and the cluster engineer.

2.3 Tarangambadi Model

In the owner-driven approach, the major responsibilities for the construction of houses rested with the communities as they had to hire labour and procure construction materials. In many such projects, the lack of supervision and technical support have produced serious issues with regard to the quality of construction. Self-help labour is not free: if it were not employed in the project it might be used to earn income in any case. In cases where technical assistance is provided, the cost of the assistance is not accounted and the financial benefits of the owner driven projects are greatly overstated (Skinner, 1984). Regarding reconstruction projects in Indonesia, using community-based development, some communities have achieved extraordinary results while others have felt overloaded and charged with too many responsibilities (Steinberg, 2007).

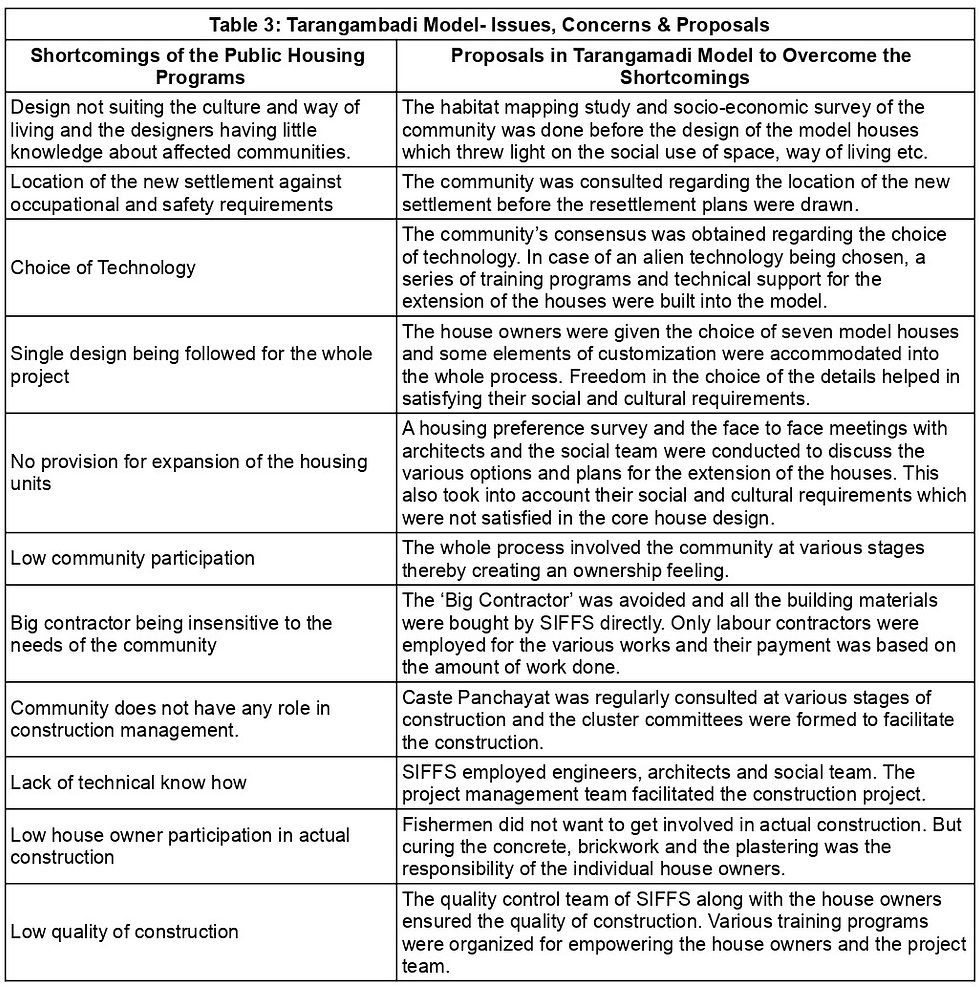

In the contractor driven approach, professional construction companies take over the entire construction. Mostly, the labour force will be recruited from far away places and the technology chosen to make use of reinforced cement concrete (RCC). This method is chosen because it is considered the easiest and quickest way to provide housing. Large-scale contracted construction tends to adopt a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach which means that the specific housing needs of individual communities are not met and diversity within the community is not taken into consideration (Barakat, 2003). The shortcomings of the public housing programs as seen in the literature are given in Table 3 below along with how the Tarangambadi Model tried to overcome them;

There is an increased user satisfaction in the owner driven model since the house owners built what they required in the way they needed it and according to their own timetable and resources. There is total house owner participation in which the house owners had full responsibility for their own choices. However, the following table explains the reasons for not attempting the big contractor driven model or the owner driven model in the case of Tarangambadi.

Arnstein (1969) in his article had described a typology of eight levels of participation. For illustrative purposes, the eight types are arranged in a ladder pattern with each rung corresponding to the extent of citizens' power in determining the end product (See Figure1). In the case of the Tarangambadi Model, empowerment of the community was targeted within the overall development context through participation at all levels. To facilitate this the following approach as given in Table 5 with reference to community participation was visualized.

2.4 Habitat Mapping Study & Socio-Economic Survey

To facilitate the planning of the new settlement, a detailed habitat mapping study was conducted which looked into the use of building materials and techniques used in the traditional houses, use of spaces, the lifestyle of the inhabitants, settlement patterns etc. A socio-economic survey examined the social and economic aspects of the community and their aspirations. The major findings of the study which have direct implications on the design of the habitat were;

The person cooking always faces east.

Most houses had a pooja (prayer) room. No one sleeps in this room even if the house is small. In addition to putting the pictures of Hindu gods, they use it for storage of water, grains & other belongings. The pooja room always faces east.

Many house owners had outdoor kitchens.

Based on their beliefs, the front and back doors are found to be in a straight line.

More than three-fourths of the families wanted to live near their old neighbours when they are being relocated.

Storage of firewood and water is of great importance.

Streets form a major part of their social life. People sit on the verandahs abutting the streets and discuss everything from fishing to politics. Kids play in the streets which are generally free from vehicular traffic and therefore safe.

The fishermen Caste Panchayat has a major influence over the community in all matters that pertain to the village as a whole and therefore they enjoy a great deal of power.

Only a small percentage of the houses had toilets.

The experiences of the Government Housing Scheme done 20 years ago did not create a favourable impression about the public housing projects.

2.5 Management of the Project

The construction work assigned to a big contractor is usually centrally controlled and managed; he/she may be reluctant to make any changes, as it will involve cost overrun to do the additional work. House owners will not have a say in the construction, especially if they were to be subsidized. The person in charge of construction at the site has no freedom to make any changes because of the terms of the agreement in the contract and every detail is frozen even before the commencement of construction.

In contrast, SIFFS decided to avoid the use of big contractors in the reconstruction project and adopted the labour contract method. The construction materials, scaffolding & centring materials etc. were arranged by the SIFFS Project Team while the construction was done by labour contractors whose team sizes were much smaller.

2.5.1 Selection of the House Owners

As per the Government Policy, the norm was that one housing unit was to be provided for a house and not a household. Those who had vacant plots were not eligible for a new house or those who had a joint family living in a single house were eligible only for one house. The selection of the house owners was done as per the list given by the Caste Panchayat for each cluster before the construction started. Since the habitat mapping studies were done in the initial stages, false claims were easily verified. The guideline was that whoever was closer to the sea in the old village will be so in the new layout. In addition, the majority of the house owners wanted to be near their old neighbours to retain their social relationships.

Before the construction started, the house owners were informed about who their neighbours were and the exact location of the plot. All the house owners met at the site along with the representatives of the Panchayat. Many differences were sorted at this point and changes were facilitated with consensus.

2.5.2 Cluster Committees

The Cluster Committee was assisted by the Cluster Volunteer who was a family member belonging to that cluster. He/She acted as a link between the house owners of the cluster and the construction team. Though the Committee consisted of both men and women, by and large women attended meetings regularly.

Meetings were held at all stages with the house owners on a cluster-wise basis. In addition to grievances, doubts regarding technical issues such as the depth of the foundation required or the feasibility of using stone for the foundation etc. were discussed in these meetings. In one of the meetings, a lady enquired whether SIFFS was paying the contractors on time. In fact, the labour contractors were not paying their workers properly and they used this as an excuse for the slow progress of the work. It had to be cleared with the house owners and the Panchayat that this was wrong information. Thus the cluster meetings helped in strengthening the rapport with the beneficiaries.

2.5.3 Training Programme for the House Owners

When an alien technology was used for the reconstruction project, the community should have the funds and skills to maintain the buildings safely without outside help (Barakat, 2003). Training programmes at all levels are required for empowering the community and the various building workers for making the right decisions and for helping them in extending and maintaining the houses. An exhibition with materials and explanations in Tamil (the local language) and a series of training programmes were conducted. The first meeting of the cluster covered the following topics

The options with the advantages and disadvantages

Choice of materials and techniques

The overall process and their role in the construction

The selection of the cluster committee

The selection of the cluster volunteers

Any doubts and clarifications sought by the house owners

The training programme of the house owners on the technical aspects covered the following topics

Safety aspects

Importance of quality in construction

Quality of materials

Technical aspects of concreting, brickwork, plastering, flooring etc.

Their role in ensuring the quality of construction and their participation.

The involvement of the house owners in the actual construction was in curing of the concrete, brickwork, plaster etc. The awareness created during the meetings on the strength of the concrete is dependent on the curing helped as most of the house owners participating in the curing process.

2.5.4 Involvement of the Caste Panchayat

Major decisions were taken at every stage of the project in consultation with the Caste Panchayat, such as regarding the choice of technology, the layout of the village, changes to the model houses etc. while the rest were left to the choice of the individual families. There were times when the role of the Caste Panchayat became very useful in making crucial decisions and the community as a whole accepting those decisions. For example, one house owner passed away while the construction of his house was going on in the new settlement and he had no descendants. In this case, Caste Panchayat came forward and allocated the house to another family.

3. Community Participation in Action

3.1 To Move or Not To Move From The Old Site

During the tsunami, the low lying northern part of the village mostly occupied by the fishermen suffered near-total damage. The houses in the historic southern part (Danish settlers of the 17th century had built the houses and other public buildings) which are more elevated and with thick vegetation and less density, suffered much less in the tsunami.

The issue of moving out into the new settlement raised many doubts and questions amongst the community once the relief period was over. “The issue of relocation boiled down to a fundamental dilemma that fishing communities everywhere faced; life security vs. livelihood security” (Venkatesh, 2006). Fishermen cannot live very far away from the beach because their activities are directly linked with the sea. Relocation far away from the beach may negatively impact the following activities.

Community activities such as keeping the boats and engines, drying fish, repairing the nets, etc. take place on the beach.

The fishermen have to go into the sea at odd hours.

Auctioning and selling fish- It is mainly women who are involved in the auctioning and vending of fish. Once the boat reaches the shore, women of the family take over.

There will also be unplanned trips to the sea-based on others’ catches.

The Beach is the main social space and recreational area for the fishermen.

However, the concerns which prompted the fishermen to take a decision to move away from the existing location were the following;

The belief is that the houses in the new location will be safer from the natural hazards since the distance from the sea will be greater.

Fishermen have been living near the beach for generations. In most cases, there were no proper documents showing the ownership of the land to an individual. Moving to the new location will ensure proper security of ownership.

Moving away from the sea might make the water availability better because, in the coastal areas, the groundwater has turned saline over the years.

Two House Theories –Many beneficiaries assumed that they can retain their existing house as well as make a claim for a new house – one house for livelihood and the new house for safety.

3.2 Negotiations by SIFFS with the Community

A hazard map was prepared by SIFFS to ascertain the safety of existing and new settlements of Tarangambadi that would be submerged for different levels of water inundation above the mean sea level. Further studies showed that certain areas in the existing village were safer than the low-lying new site identified for construction as far as the risk against natural hazards was concerned. Hence, SIFFS decided to rework the strategy towards the reconstruction of the houses. The safety of the new location, as well as the existing village, was discussed with the community and they were made aware of the risk involved for those moving into the new site. The dangers involved in living in high-risk areas in the existing village were also effectively conveyed to the people. The following understanding was arrived at in consultation with the Panchayat and the community.

Houses that are within 200 meters of the high tide line will be relocated to the new site. The new site identified for reconstruction is low-lying where water stagnates during the rainy season to be raised by filling.

Owners of houses beyond 200 meters can choose between in situ and new sites. If they choose the new site, they will have to relinquish the existing house and site, which will be used for common purposes such as widening the road or allocating to those in-situ house owners whose extent of the land is less than 3 cents.

Those who want to keep their existing houses and preferred repairs and improvement can do so accordingly and SIFFS will help them in getting the government assistance for repairs.

There will be an attempt to give a minimum of three cents for each family and vehicular access for each plot in the existing village. Drainage, sanitation and the roads will be properly planned. Common amenities and public buildings will be distributed in the existing and the new site according to the distribution of the population and the future planning of the village.

If one has to build in the high and medium risk areas, the ground level and the plinth level will be raised to make the building safer.

With the assistance of the Government, proper security of tenure and ownership will be ensured to the house owners who are staying in-situ.

Based on the above guidelines, there was a drastic change in the choice made by the people towards shifting to the new site. The majority of the people wanted to stay in the existing village itself. Some of the following considerations have led to the rethinking of shifting to the new site.

The people realized that they would not be permitted to have two houses.

SIFFS agreed to assist the house owners in getting government assistance for repairing their existing houses. The incentive of getting 3 cents and a house worth Rs. 150,000/- was found to be unattractive for those who were having good quality houses and large plots.

Those who owned more than three cents did not want to relocate to the new settlement, because they are eligible for a new house in the existing location itself.

3.3 Participation of the Community in Site Planning

3.3.1 Re-planning the In-situ Settlement

The in-situ clusters were re-planned since some of the house owners were moving into the new settlement and vacant plots were now available. In some areas where the housing density was very high, negotiation with a few house owners to move into the new settlement proved successful. This land was redistributed amongst the people who stayed behind so that they too obtained three cents of land. Those house owners who had more than three cents before the tsunami continued to enjoy the same extent of land. Streets were widened facilitating vehicular access to the maximum number of plots. The role of the Caste Panchayat and the cluster committee in the re-planning of the land was significant.

In one case which is close to the temple, there was no possibility of increasing the size of a plot to three cents because the Caste Panchayat objected to reducing the width of the street as the temple procession goes through that street once a year. The owner was given an option to move into the new settlement, but he preferred to stay back saying that it is auspicious to be near the temple. In another case, the house owner found that the side setback was very little once the house is built. He negotiated with the neighbouring landowner and purchased sufficient land so that he could have the house of his choice.

3.3.2 Design of the New Settlement

There were two layouts made for the design of the new settlement – one which was based on the gridiron layout and the other cluster layout. The density of the houses was less in the case of the cluster layout because of the additional common spaces given in a cluster. This common space can be used by the members of the cluster layout (8-12 houses) for children to play, vehicles to be parked, for any special occasions etc. Both the layouts were marked on the ground with the streets and plots. It was surprising to note that the Caste Panchayat decided on the gridiron layout and the reason given was that it would be difficult for them to control the encroachment on the common spaces if the cluster design opted.

The new gridiron layout may not be in tune with the organically evolving settlements of the fishermen villages, but in the case of Tarangambadi, the gridiron pattern was followed by the Government 25 years ago for the construction of about 400 houses. The historic part of Tarangambadi which is the Danish settlement followed a gridiron pattern. Hence the Caste Panchayat of Tarangambadi was quite familiar with the layout. In the existing village, the streets are very much a part of the traditional lifestyle with children playing in the streets and facilitating social interaction.

3.3.3 Common Facilities

Children’s play areas, women’s community centre, pre-school facilities, parks, rainwater harvesting tank, bus shelters, land provision for future housing etc were provided as common facilities in the new layout. In addition, a green space equivalent to the size of two plots was provided. This was intended as a play area for children, also offering some shade and absorbing or draining off rainwater. For every 30 plots, such a provision was made.

The community also requested facilities that were extremely essential such as a community hall which they can use for weddings, receptions etc. and an open-air stage near the temple for public meetings and festivals. In addition, the Caste Panchayat raised the demand for a memorial for the victims who died during the tsunami. One of the places suggested was close to the entrance of the village, but there was no suitable land available. An alternative way to mark the area near the beach since all the fishermen families were relocating beyond 200 meters from the high tide line.

3.4 Participation of the Community in the Design of the House

In the case of most mass housing projects, a prototype model is introduced which is based on the assumption of occupancy by a nuclear family. In the case of Tarangambadi, many families were extended families and they were living in large houses compared with the size of the house they were receiving. The requirement of each of the families may vary depending on their needs and aspirations. It was therefore decided to construct full-scale models as discussions with the community showed that they were not able to understand the drawings or small cardboard models. The house owners’ participation in design becomes meaningless if they are unable to comprehend all the dimensions of the design.

The six model houses constructed helped the communities evaluate the designs and suggest the modifications that they wanted. User participation in planning is facilitated by having various options to choose from. “The greatest degree of community participation is seen in projects in which planning (decision making) is added to the implementation and maintenance spheres of collective activity” (Skinner, 1984). A rammed earth house was added as Option 7 to promote the use of alternate technology. Each house owner was given the choice to select a model based on his/her visit to these two sites. The community studied the model houses and provided useful comments. They include;

Lack of built-in shelves inside the houses for storage. There were no shelves in the model houses because SIFFS wanted to use model houses for other purposes after the construction project was over. It was decided that a minimum number of shelves will be given as part of the fixed cost of the house, while the rest will be made optional.

Many raised doubts about the continuous sunshade being given at the roof level. They suggested flat sunshades above the openings. Their argument was that the water will enter the house through the windows when it rains. Finally, it was decided to leave it to the individual house owner to decide.

People had raised concerns about the orientation of the kitchen and the position of the rear door etc. They were convinced that during the design of the individual houses, the specific requirements of the family such as the position of the firewood Chulah (stove), the pooja room etc, will be taken into consideration.

The Caste Panchayat wanted an RCC framed structure instead of the load-bearing walls for the model houses.

3.4.1 Selection of Models by the House Owners

Once the clusters were formed, a housing preference survey was conducted by the architectural and social team. Details such as the preference for the various options, setbacks to the houses, expansion possibilities, location of the toilets & kitchens, provision for shelves, owners’ contribution of doors & windows etc. were collected at this stage. The architectural and social teams met every house owner and their family members. Customization of each house was the outcome of such meetings. Detailed drawings including the site plan and the future expansion were made for each of the houses. The options chosen by the house owners are given in Table 6 below;

Option 2 was the most popular choice. This perhaps could be due to the following reasons;

It had four small rooms without a verandah and suited the requirements of the larger family as well as those who do not have the resources to extend their houses immediately.

Although they wanted a verandah as shown by the socio-economic study, most families thought that they can add a verandah using impermanent materials at low cost.

This satisfied their social and cultural requirements such as the pooja room, the front door and the rear door falling in a straight line, etc.

This resembled the plan of their traditional houses more closely than any of the other options.

Option 3 was a model which is two-storied and developed for areas that have high risk in the existing village or if the plot size is very small. None in Tarangambadi chose this option in Phase I. A significant number selected Option 4 because the design included a verandah (Option 2 and Option 1 do not have verandahs in front) with arches. They seemed to like the elevation of the building because of the arches. However, there is no pooja room for this design and those who wanted a pooja room opined that they will add it at the back as an extension later.

Option 1 is the only model with an attached toilet. Generally, the more affluent and the educated among the fishermen chose this option. Some of the families chose this on the condition that the entrance to the toilet should be provided from outside. In this option, the front and the rear door was not in a straight line, but most of the house owners who chose this option shifted the door so that they fell into a straight line. No house owner selected Option 5, while only one house owner chose Option 6 as the basic unit since the living room was the biggest. The probable reason could be that none of the house owners took the trouble to visit Option 5 & 6 houses, as they were built in a different village. The reasons for the choice of rammed earth construction by nine house owners (around 10% of the house owners) in the initial stages could be based on the following assumptions;

A model building was constructed in rammed earth and it has withstood one of the worst monsoons during the last century in November-December, 2006.

The RCC roof on top increased their confidence that the rammed earth buildings were quite durable.

Option 7 gives an extra plinth area with no additional cost.

However, these house owners changed their choice to other options due to the non-delivery of the rammed earth options.

3.5 Participation of the Community in Choice of Technology

An RCC framed building would have concrete footings and concrete columns and beams. The load is transferred through the column beam frame to the RCC footings. The masonry walls do not take the load and are constructed only after the frame is over. Load-bearing masonry building transfers the dead and live loads of the buildings through the masonry walls and footings. The walls are structural members in this case. The community was very much influenced by the reconstruction of houses by other NGOs in the neighbouring villages. The demand for the RCC framed structure itself was because those villages which started construction earlier used RCC framed construction. The following reasons could be attributed to the selection of the RCC framed structures by the community;

There were already some houses with load-bearing structures of RCC roofs in the village before the tsunami. They would have thought that this will give the extra protection that they require against natural hazards.

Most of the houses constructed in the cities and by the affluent were using RCC.

They believed that the use of this technology will give them more status since their notion was that the local building materials and techniques were associated with backwardness and lack of modernity.

The use of local construction knowledge allows for better maintenance and thus greater sustainability as well as enabling incremental upgrading and expansion. The material used is more likely to be culturally and socially appropriate, as well as being familiar (Barakat, 2003). Many house owners knew that the reinforced cement concrete structures were not comfortable from a thermal point of view compared with their traditional houses built of thatch and tiles. Their argument was that the extension to their houses will be done using the local construction knowledge, skills and materials. Many of them had kept the materials salvaged from their damaged houses for future extensions.

If modern materials and technology are used for the reconstruction of the houses, then the user participation in the execution of the project has difficulties (Turner, 1972). The Tamil Nadu Government Technical Guidelines which was released in April 2005 was a constraint as far as this aspect of the project is concerned since it advocated only for the introduction of reinforced cement concrete slab for the roofs of the reconstructed houses. The local building technology, context, wider environmental impact of the technology, cost-effective techniques, alternative materials, the sustainability aspects and the technical capacity were completely ignored in the guidelines which the NGOs were supposed to follow.

This kind of community participation also enabled the beneficiaries to suggest modifications while constructing. Customization related to the location of the house within the plot, choice of flooring, changes in the interior space, external elevation, scope of expansion etc. Consequently, though with unavoidable delays the first phase of the 451 houses was handed over to the beneficiaries in May 2007.

4.0 Strengths and Limitations of the Project

The habitat mapping study and the socio-economic survey facilitated formulating a strategy for reconstruction with community participation. The preliminary studies helped in creating a good rapport with the people and they endured the delay for the following reasons

They felt that if the construction is done fast, the quality of construction may suffer.

They trusted that SIFFS will be able to deliver a better product compared with the neighbouring villages where similar projects have been implemented. The presence of the primary fish marketing society and the boat building yard of SIFFS before the tsunami was a positive factor and this will continue even after the completion of the housing project. The participatory approach in design and construction were welcomed by the house owners.

The new settlement replicated the earlier pattern of the neighbourhood as much as possible.

Both the Caste Panchayat represented by the leaders and the individual house owners had effective roles in the reconstruction process. Building with labour contractors helped the local economy. The cost of supervision and monitoring was minimal as people actively participated in management. The strength of the technical team and the continued presence of SIFFS before and after the reconstruction assured the people of rehabilitation. Choice of technology was community driven and in spite of training programmes proper maintenance may be of concern. Individual customization and community participation delayed work and also required persistent efforts to convince people. Consequently cost escalation was inevitable. The replicability of the project is the best indicator of the success of the project. This is yet to be examined.

5.0 Summary

In summary, one can refer to Cockburn & Barakat (1991). “‘Settlement reconstruction’ is an ‘incremental learning process’ by local people who have to learn to ‘grow it’, and for themselves ‘to grow with it’. The product, the ‘new’ settlement, has to belong to those who live in it. This ‘sense of place’ and people’s ‘sense of belonging to it can only be fully realised over time but we believe it can be planted right at the beginning by putting the responsibility with the prospective inhabitants through their involvement.” The SIFFS approach attempted to achieve this form of integration.

To see more photos of the completed houses and to know more about the project, click the following link:

شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

الشيخ الروحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني مضمون

Berlinintim

Berlin Intim

جلب الحبيب

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://hurenberlin.com/

youtube